There was much excitement in Brussels this week with the publication of ‘Plan S’, the European Commission’s plan to make all scholarly publications resulting from public research funding open access from 1 January 2020.

But the big question is: what happened to Plans A-R? Robert-Jan Smits, Senior Advisor on Open Access within the European Political Strategy Centre, spoke exclusively to Fundermentals.

‘It was a long and difficult process,’ suggests, Smits, ‘and it took us many months and an awful lot of coffee.’

Smits set out the process that they had been through to reach Plan S, and the 18 previous plans that got them there.

Plan A: we began optimistically, and suggested that everything should be free. What we were suggesting was, if you will, a research ‘summer of love’. Nothing would be paid for. We’d live in open access communes, sharing everything. No hell below us, above us only sky. That sort of thing.

Plan B: The Court of Auditors put a stop to that, and said that absolutely everything should be paid for, including the flowers in our hair.

Plan C: There was something of an impasse. I wouldn’t say it was necessarily like the Democratic Convention of 1968, but it was like the Democratic Convention of 1968. But with less tear gas and water cannons. More coffee was drunk, and everyone sat around surreptitiously checking their Facebook updates.

Plan D: We began again. This time there was the suggestion that there should be an information ‘single market’, within which there should be the free movement of information. However, members could choose to trigger ‘Article 50’ and leave this OA market at any time.

Plan E: The UK triggered Article 50.

Plan F: We began negotiating with the UK about the OA relationship we would continue to have with them. They said that they wanted to continue to benefit from any OA arrangement, but would rather pay to do so and not have any say in the negotiations on future developments. We were somewhat perplexed, but agreed.

Plan G: At this point the publishers responded to our plans. They said that they were very much in favour of OA, but only if both producers and users paid for it.

Plan H: We suggested that this was going against the principles of OA, but they said that this was very far from the truth. Rather, they were enabling it to happen, but obviously had to cover the cost of the free writing, free editing, and free reviewing that they were having to undertake. They suggested that there should be a ‘titanium OA’ system, whereby both producers and users pay, and the embargo period be extended from six months to 100 years.

Plan I: At this point we ordered more coffee.

Plan J: We started again, and told the publishers that any fees would be capped, and that we would decide what that cap should be. They seemed to think this was an opportunity to barter with us, and suggested that, ‘as it’s you, I can do it for £1m an article. But you’re killing me here, you know? It makes me weep. I’m practically giving it away.’

Plan K: We ignored them, saying we’ll deal with it later. We had more important things to deal with. We had to craft the principles by which the new system would be developed. Naturally, we had to decide how many.

Plan L: This was where there was the most robust negotiation. Should it be five? Should it be 20? The UK suggested that we should move away from any decimal system and have a nice round 6.0761, which was exactly how many feet there were in a fathom. However, as they had already said they didn’t want any say in future negotiations, we ignored them.

Plan M: The publishers said they ‘could do us’ 10 principles for the cost of five, but only if we signed up now. It was a time limited offer. They would throw in a free tote bag. We ignored them.

Plan N: We agreed a nice, decimal 10. Ultimately it didn’t really matter what the 10 were as long as there were 10.

Plan O: We drafted some words to fill in the 10. Really, don’t bother looking too closely at them. They’re all there, and roughly in the right order. They are – as we say in Brussels – ‘aspirational’.

Plan Q: So we had a rough plan, but we had to get funders on board. No problem with 10 member states, but for some reason Germany was holding off. and the Benelux countries could only do Nelux. It wasn’t ideal, but we thought – as Meatloaf very nearly said – 10 out of 28 ain’t bad. Plus Norway, but I don’t think that was part of Meatloaf’s original song.

Plan R: At this stage we realised that we hadn’t actually got the Commission’s buy in to the plan. It had ‘expressed support’, and well, given the time it takes to get things approved in Brussels, we thought, f*ck it, that was good enough.

‘It was actually a very streamlined and quick process – for the European Union,’ concluded Smits. ‘I mean, we were set for a Plan Z, so a Plan S is a real result.’

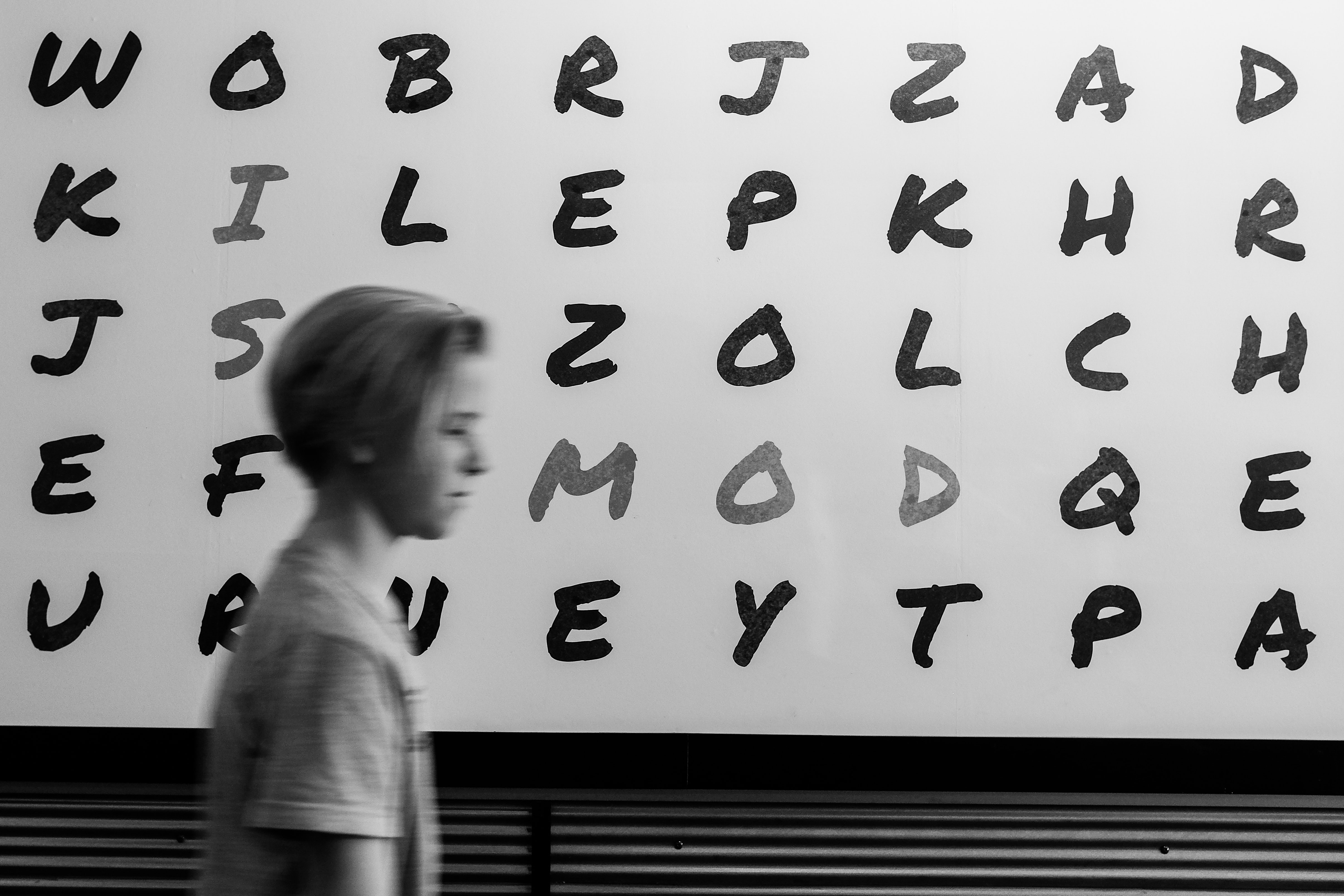

Photo by John Jennings on Unsplash