We’ve all received them: long, rambling emails with a detailed preamble that would make Tolstoy blush, a vaguely officious tone and the main question buried deep in the 32nd paragraph.

Worse still, we’ve all written them. So how do we stop doing it, and get people to read our messages and respond to them?

The art of writing a good email isn’t a million miles away from writing a good grant proposal. You should start with your audience.

Will they be reading it at their desk? On the train? On a screen they have to scroll down, and down, and down? Will they be darting between meetings, or ploughing through their inbox at the end of a long day? Will they be trying to write an article while cooking dinner and feeding the baby?

They’re probably trying to do a million things, so be kind to them.

- Keep your email short. Really, it should be a couple of paragraphs at most. If you need to explain something in more detail, use the inverted triangle.

- Use the inverted what?? The inverted triangle. This is an old journalistic technique. A reader’s attention steadily declines as they read through a news article, so journalists are trained to put the most important message at the top. For a newspaper, this is the who, what, where, when and why of a story. For an email, it’s the key point you’re making or question you’re asking. If the reader only gets as far as the first line, then at least you’ve got the message to them. The Tolstoyan context can come later.

- Keep it simple. Just because you’re talking to intelligent people, it doesn’t mean you have to use long words or convoluted sentences.

- Keep sentences to around 15-20 words, and paragraphs to 2-3 sentences. You can vary things, of course, but this is a good rule of thumb.

- Try to have only one main idea per sentence.

- Avoid jargon and explain technicalities.

- Use the active rather than the passive voice. So, for example, you should say ‘the panel rejected the application,’ rather than ‘the application was rejected by the panel’. Ideally you should say neither, of course.

- Use ‘I’, ‘me’, and ‘you’, not ‘the University,’ or ‘the applicant’.

- Use clear formatting. Use bullet points. Use bold type to highlight key messages. Break up paragraphs with a space, and don’t be afraid to use subheadings.

- Make the title relevant. Ideally, write it when you’ve written the rest of the email. That way it will be a summary of your point, not a launch pad for it.

I know: it all sounds easy, but it’s often harder to write simple messages than it is to write complex ones. But it’s worth it. If you manage to keep it short and simple, with the clear takehome message at the top, there might just be a hope that that academic, juggling an article, a baby and dinner, will read it. Better still, they might respond.

This was first published in Issue 10 of Arma’s Protagonist magazine, and is republished here with kind permission.

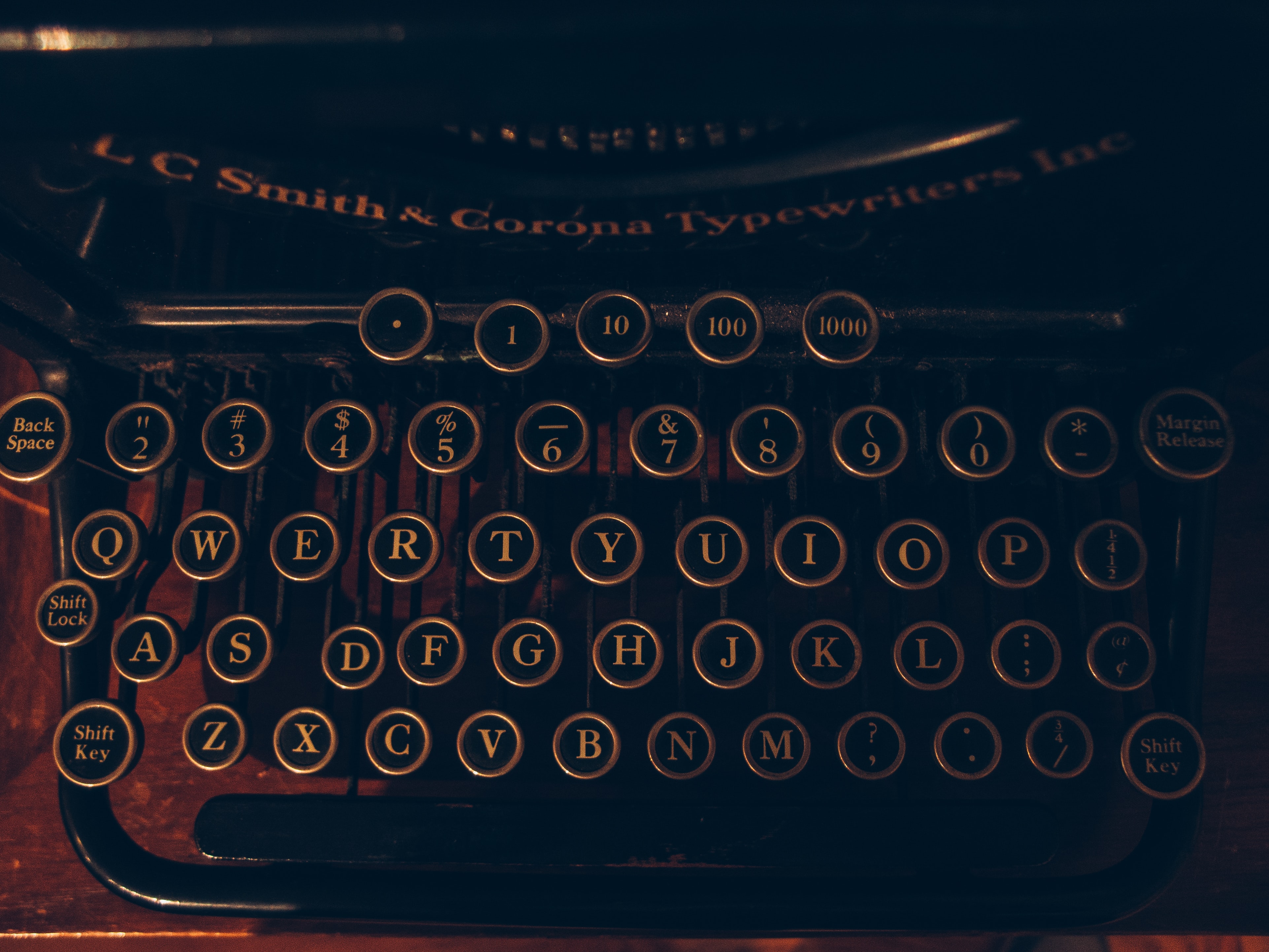

Photo by Andrew Seaman on Unsplash